Archosaur Air Conditioning

Today on DrNeurosaurus I want to talk about a study that came out in July of this year but has recently been circulating in the media. This isn’t the typical study I discuss, where a new fossil is discovered, described, and celebrated for its novelty and scientific value. This is a different kind of study.

The authors wanted to take a closer look at a structure in the head of many archosaurs. You might remember archosaurs from other posts—they’re a group of animals that include living crocodylians and birds, their common ancestor, and all of its descendants:

IMAGE 2019-09 archosaurs-phylogeny-from-archosaur-musings.jpg

Caption: This tree is modified from the one found here, on Archosaur Musings.

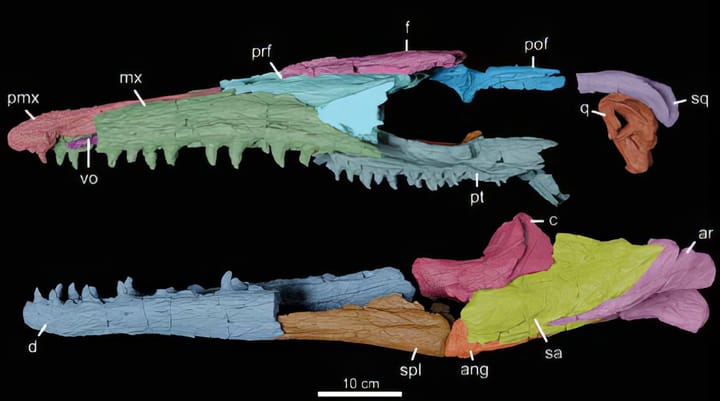

All of these animals have openings in the top of the skull that previous scientists thought were home to jaw muscles. The authors examined these openings in over 100 specimens of lizards, turtles, crocodylians, and birds using CT scans, MRI, dissection, and other methods.

IMAGE 2019-09 crocodilian-skull-source-unknown.gif

Caption: A crocodylian skull with the openings labeled in the top of the skull. Source unknown.

They found that in many cases, the openings didn’t contain muscles all the way through. Instead, the openings housed blood vessels just under the skin. When the authors looked at extinct animals like non-avian dinosaurs and extinct crocodylians, they did not find evidence of muscles in those locations. Using comparisons with living animals, they suggest that these openings likely housed blood vessels instead. But for what purpose?

That depends on the animal. In animals with display structures like frills, those blood vessels could have provided nutrients to the structure.

IMAGE 2019-09 triceratops-NHM.jpg

Caption: A Triceratops. Its frill is a display structure—a structure used to communicate with other members of its species. From the Natural History Museum, London.

In animals without those structures, the blood vessels may have functioned in regulating body temperature. To test this idea, the authors used thermal imaging cameras to photograph living crocodylians. They found that those openings were cooler than the surrounding body in hot temperatures and warmer than the body in cool temperatures. This suggests that their hypothesis has support.

IMAGE 2019-09 Fig-11-thermal-art-brian-engh-1024x657.jpg

Caption: Figure 11 from the paper: an artist’s rendition of thermal images of Daspletosaurus, Deinonychus, and two croc-line archosaurs. By Brian Engh.

By using numerous specimens and multiple imaging methods, the authors were able to uncover something new about animals we’ve known for a long time, including species that are still living today.

Comments ()